Oh life, college students love to hate you. Sometimes you go in our favor and we’re eternally grateful, but most of the time you really seem to screw us over. But what exactly is life? Sure, we can say it’s living a long time or making the most out of every day, but that’s also just how our culture sees it.

Life, and the values it encompasses, is a concept defined medically, symbolically, physically and socially. The definition of the value of life differs between individuals and essentially comes down to one question: What does it mean to be human? Many scholars weigh in on this, using fancy terms like biopolitics and bioethics to grab the reader’s attention and for the most part it works. Let’s face it: “Bio” words play a large part in the making of human experiences and how the value of life is much more of a social concept than anything else.

When the average person thinks about life, it’s mostly about how long they’ll live or if they regret anything up to this point. But there is such a thing as the “art of living;” something dating back to the wealthy men of ancient Greece.

In relation to modern times, not everyone has access to healthcare or other life necessities that create the “art of living.” Basically, those in poverty will have a decreased value of life and it all comes down to economics: “the amount we will pay to keep somebody alive” (Marsland and Prince).

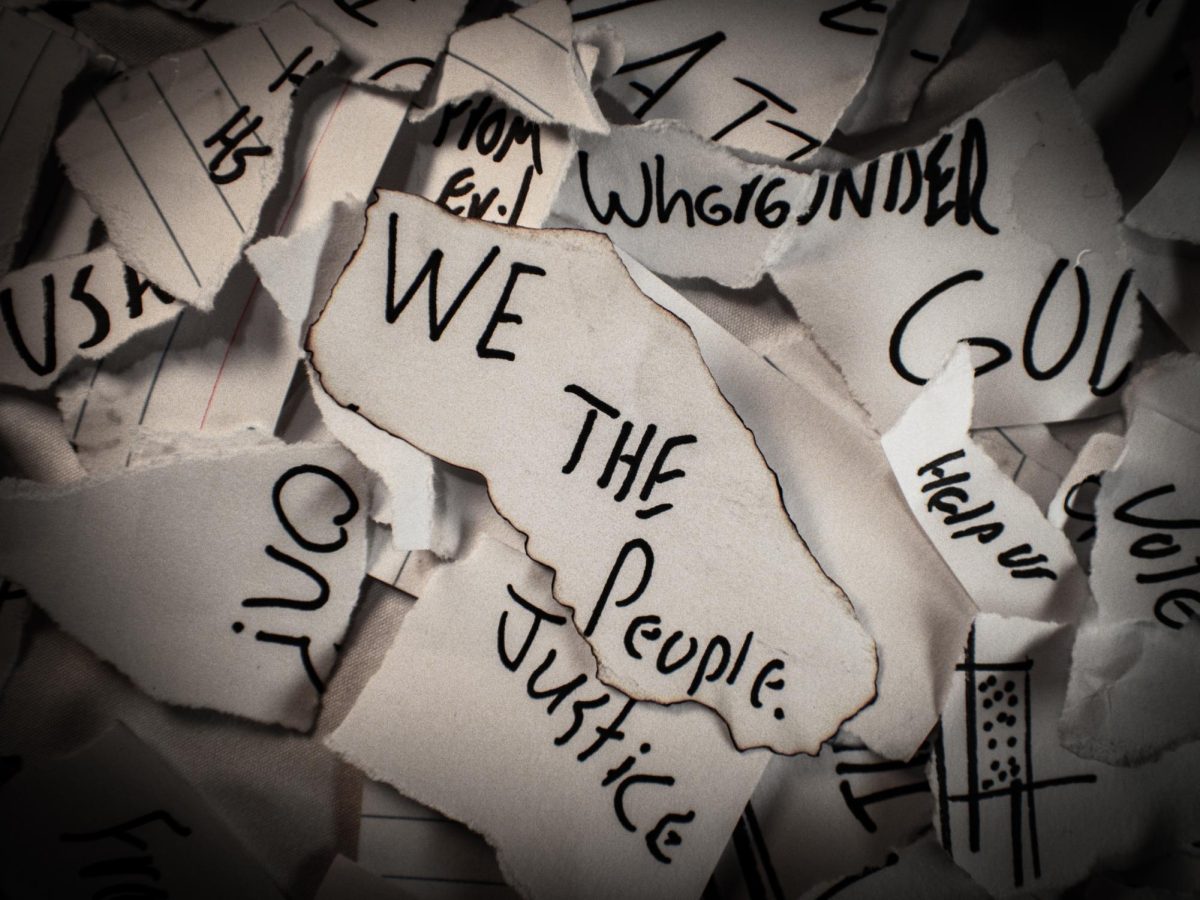

Most of us already know this quote to be true. Some of our classes mention the structural inequality faced by American youth of all ages and others look at that inequality in more detail. Even now, our politicians debate on the availability of healthcare in Washington, D.C. at the same time our Political Science classes hold in-class debates over the same issue. Everyone is guaranteed the right to this life, but it seems not everyone is guaranteed to master the “art” of it.

Selective reproduction with humans isn’t uncommon, nor is it recent. Ancient civilizations left weak children in fields to die and now women can have an abortion should they so choose. In animals, sick newborns are abandoned. Essentially, survival of the fittest. When applied in a social context however, the “life worth living” becomes an entirely different matter.

The value of life is a cultural universal, even if different groups show that differently. In Denmark, the worth of life is studied in neonatology. Svendsen covers this topic in depth, going as far as doing a cross-study between human infants and test piglets in laboratories. Because the “lives of animals are entangled in improving the quality of life for humans” (Svendsen), it’s important to see the overlap this cross-study presents.

Denmark has plenty of involvement in the birth of infants, going as far as offering contraceptives to women with social and/or psychological problems so they do not reproduce. Alternatively, piglets are tested in the laboratory for the purpose of making sure human infant lives can be enhanced.

By matching preterm piglets with the due date of certain preterm infants, researchers are able to find and test different variables in order to ensure preterm infants have a high quality of life; strong kinship ties between newborns and their families are created and the moral concept of life becomes one of how strong familial ties are.

Tying this back to poor families, it can be said their value of life is morally high because they may have strong family ties from the need to rely on each other. However, family ties don’t create a high economic value of life, which brings everything back to the starting point.

Is it possible to weigh the moral value of life against the economic for a true answer? Think about it in our own setting here at Bloomsburg: Are you here because you love your major (morals), or are you here because it’s a guaranteed way to make a living (economic)?

The social concept of life and its value plays a great part in what makes us human because social settings and the way a society operates drastically impacts how those in poverty live their lives.

Society places emphasis on the way our value of life contributes to the larger picture. This is seen in the way the upper class treats the poor: Without the funds to afford the things that make a life worth living, society deems those in poverty to a low value of life. Don’t believe me? Turn on the news.

Rachel is a Junior Anthropology major. She is a member of Phi Sigma Pi and the president of the Bloomsburg Anthropolgy Club. She is also an on-campus tutor.