A student’s experience detained in Isreal and Jordan

September 5, 2019

In early July I was detained at the Allenby Bridge attempting to travel from Jordan to Israel for the wedding of one of my professors who is Palestinian.

I was told by Israeli border officers that I could not enter because I was “disorganized” and it was “unlikely” that a professor would ask me to attend their wedding. Obviously their reasoning was arbitrary. Ultimately I was denied entry into Israel and shortly after wrote about the episode.

I have had a lot of time to reflect since I last wrote about what happened and some minor developments have taken place. When I returned to Jordan where I was stranded for three weeks, I fired off over a dozen emails asking for assistance from my Senators and the State Department.

Most were followed by the common reply, “I’m sorry, but we cannot do anything to help your situation.” Senator Bob Casey’s office wrote me a full month after I contacted them with a four sentence email that my detention abroad was “beyond his jurisdiction” and that “they hoped I understood their position in this matter.”

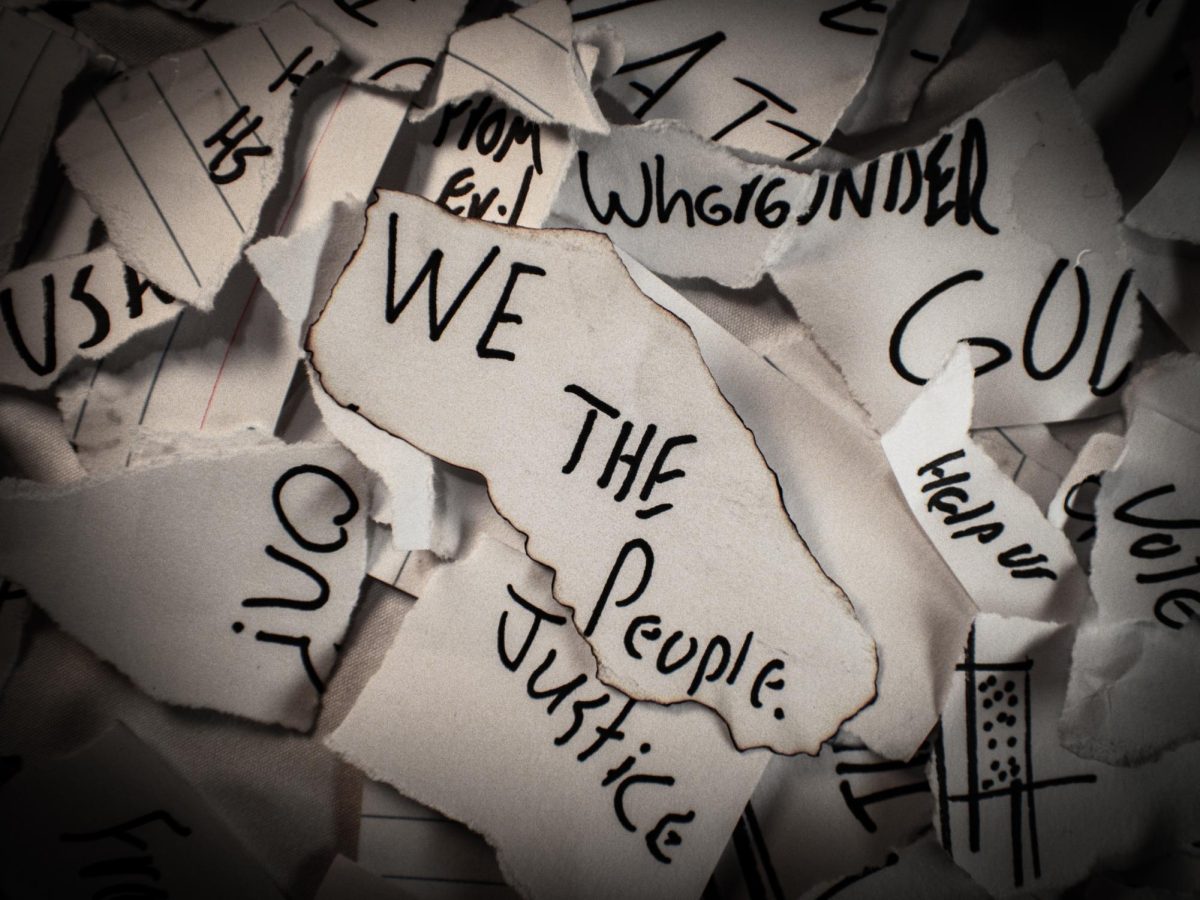

I felt abandoned. Yet, I knew my situation was not unique after I received a letter from the U.S. Embassy in Jerusalem stating that this is not the first time such an incident has happened to an American citizen. The only solution offered was that I could write a complaint to the Israeli government.

Writing a complaint letter is not going to erase the trauma and abuse I endured for hours while detained, nor reduce the frequency of this type of incident. It’s not going to erase the fact that the U.S. bankrolls billions of dollars a year to Israel whose border police carry out interrogations at the crossings not only to Palestinians, but to American citizens as well.

The seemingly indiscriminate dehumanization of any person who attempts to cross a border should not be a norm. Grabbing a tourist’s body to poke and prod at a tattoo a cross on their wrist or other body art without consent–as what happened to me–is certainly not normal.

A border crossing should not have to be traumatizing, whether you are allowed to enter the country or not.

Just this past week the Israeli ambassador of Panama Reda Mansour, who is Druze, was ordered to pull over and get out of his car when driving up the airport outside of Tel Aviv. He castigated the guards who delayed him in a Facebook post, “Ben Gurion, you can go to hell. Thirty years of humiliation and it’s still not over. You used to take us apart at the terminal, and now we’re suspects even at the entrance,” he wrote.

Clearly there is a major profiling problem not affecting just tourists, but Israeli diplomats as well. While this is just one facet of racial profiling, larger issues still remain at the forefront for non-Jewish citizens of Israel and Palestinians in the occupied territory.

After the checkpoint, I stayed in Jordan which afforded me an opportunity to connect with Palestinians living in the refugee camps in Amman and the northern city of Irbid near the border with Syria.

Walking through Amman New Camp, also known as Wihdat, tells another aspect of the Israeli-Palestinain conflict through the lens of refugees. The camp is one of the oldest Palestinian refugee camps, established a few years after the 1948 war. It is visibly more dense than the rest of Amman and buildings are in disrepair. Around 57,000 Palestinians are squeezed into the camp’s tiny grounds of .19 square miles. The camp’s lack of green space, open areas, and over-crowdedness is a metaphor for the suffocation Palestinians experience daily and will in the years to come unless something changes soon.

While it’s not feasible for each and every American to travel and witness the Palestinian experience, it is important for the stories of everyday Palestinians to be told.

Walking through the overcrowded streets of Wihdat, a group of children stop their soccer game curious if I worked for the United Nations. There was a lot of excitement. They asked me what I was doing in the camp and I stopped to kick around a ball with them in an alley.

After a quick scrimmage, other kids joined and showed me their bicycles. When this caught the attention of nearby adults, I was invited to sit with a group of older men near an outdoor fresh fruit market where merchants shouted over each other to potential buyers. Many of them were more than willing to share stories about their lives in Palestine, life in the camp, and the sense of despair and uncertainty they have felt since they fled in 1948 and settled in Wihdat in 1955. The oldest of the group, an 80 year old named Mohamed, had pain in his face as he recounted his life in Haifa as a young boy before he and his family were forced to flee. It made my heart sink.

Others shared their stories of al-Nakba and how they came to live in Jordan over date cookies and coffees. Others in the group shared more lighthearted stories, mostly childhood musings of their favorite summers spent at a grandparent’s home. While others expressed the hurt of being forced by the military to leave their childhood homes behind. Some of the adults were more hesitant to share their experience, but stayed to listen to their neighbors about a time before their lives became collectively difficult.

Later that night, when I returned to central Amman where I was staying to meet up with Palestinians at a restaurant called al-Quds, Arabic for Jerusalem. I met an older couple, Asma and Salah, who asked to join me for dinner since I was seated alone in the restaurant.

Similar stories of loss and heartbreak were exchanged over Mansaf before I returned to my hotel to leave for Irbid the next morning. Salah, with his bright silver hair and charming grandfather smile, was more than happy to share his experience during the Nakba. He and his family were originally from Lod and were forcibly expelled from the town in 1948.

Salah and his family fled from Lod to Ramallah and later settled in Jordan. He remembers trying to help his father carry most of the family’s belongings on foot all while ensuring his younger sister did not wander too far away getting lost in the crowds of people that were also fleeing Lod. Salah remembered the first day of exile and how hot temperatures were as they walked toward an unknown future.

He said, “While I was trying not to keep carrying memories of our home, I watched other families starting to throw their momentos away on the side of the road. It was so hot I preferred death than to continue marching, but my family is the only thing that kept me going.”

He had the same hurt in his eyes as Mohammed did from earlier that day. Salah shared how scared he was as a boy to walk by those who had passed away on the side of the road from heat exhaustion or dehydration.

At this point, Salah reached over to another table to grab some more napkins because I began to cry when he recounted seeing the bodies at the side of the road, some of whom where young children who succumbed to the heat.

I think the Mansaf became saltier from the tears I cried from this brief encounter with Salah and his wife, trusting me with their story so I could tell others of the suffering he and countless other Palestinians have faced. After his family’s brief stay in Ramallah, they continued on to Jordan where they have lived in exile since the Nakba.

What I witnessed stands in contradiction to the ubiquitous portrayal of all Palestinians are terrorists. This has been promoted by the highest level of the Trump administration working to arrange a peace deal. Middle East peace envoy Jason Greenblatt’s Twitter feed reflects scores of posts about Palestinians promoting terrorism, naming schools after terrorists, and paying terrorists.

At the same time there is no mention of the constant violence Palestinians experience, nor the peril faced by some 7 million Palestinian refugees, of whom 5 million receive aid from the United Nations often in camps like the ones I visited.

Treating Palestinians as criminals or an afterthought ignores the troubled history Palestinians have endured from the late Ottoman Empire to date. Regimes and rulers come and go, but throughout all of this the Palestinians have never had independence and have in one way or another lived under various forms of occupation.